GP WHO CARED FOR RUBY PRINCESS CREW SHARES HIS STORY

‘I

didn’t go looking for epidemics, they found me,’ says Dr John Parker, who was

brought in to care for the ship’s crew.

By Siobhan Calafiore

Bottom of Form

Almost unrecognisable in goggles and mask, Dr John

Parker spent every day knocking on the doors of crew members locked inside

cabins on the ill-fated Ruby Princess.

Dr John Parker.

Dr Parker was part of the medical team leading the two-week quarantine operation on board the ship before it finally set sail from Australian waters in late April.

None of the crew wanted to be there and the brief encounters with Dr Parker and his colleagues to check their temperatures were each crew member’s only form of human contact.

But the locum GP, usually based in northern NSW, was in his element.

Dr Parker outside the Ruby Princess.

He was first called away from his locum work in early March to monitor the mental and physical health of the Diamond Princess crew members in Japan, who had been taken off the ship to quarantine before they could be repatriated.

The cruise ship operator Carnival had contracted Aspen Medical, a global healthcare provider, to provide a medical team to take charge of the quarantine. Dr Parker had previously worked for the company at an Ebola treatment centre in Sierra Leone in West Africa in 2015.

After Japan, Dr Parker flew to the US to assist in what he describes as a “more technical” operation on board another of the company’s cruise liners, the Grand Princess, which was anchored in the middle of San Francisco Bay after government officials turned the ship away from the main wharf.

There were about 550 crew members on board, confined to guest suites. Dr Parker says 10 of them had tested positive to the virus, with one member evacuated after becoming acutely ill.

He eventually died.

“We had to establish a sanitised green ‘safe’ zone on board where we could sleep and again, we had to monitor all the crew members twice every day for two weeks,” Dr Parker says.

Fear of losing independence can be greater than the fear of dying

Far from his first experience with infectious disease, he had worked as a doctor in refugee camps and war zones for organisations like the Red Cross and Medicins Sans Frontieres since the mid-1990s.

“I didn’t go looking for epidemics, they found me,” Dr Parker says.

His interest in humanitarian work was initially sparked by a school visit from missionaries when he was a boy, whose stories from Africa “enthralled” him.

“The adventure has always attracted me but also the clinical work. You are dealing with primary care with no investigations — you have to solely rely on your clinical judgement,” he says.

On board the Ruby Princess, his job included testing crew members for the virus and monitoring their physical health.

But he says managing mental health concerns was one of the most critical parts of the operation.

“The crew by this stage were exhausted and some of them were very anxious,” Dr Parker says.

“They had been away from home for months and didn’t know if or when they would get back.

“These were people in a

foreign land in a very stressful situation. Some of them had loved ones back at

home who were sick, or they were worried that their families weren’t coping.”

Dr Parker says during the twice-daily temperature checks the doctors would “eyeball” the crew members to gauge their demeanour and identify those struggling with the situation.

“We would then get on the phone to them, give them a chance to download and provide them with some reassurance. They were glad to have that support,” he says.

By the time Dr Parker stepped foot on the Ruby Princess, he had already become an expert on cruise ship quarantine, having dealt with two similar situations in different parts of the world.

“We also had to bring in a second crew to service the ship, so this meant we had to train them in personal protective equipment, which they had to wear in the red zone, and supervise them.”

When Dr Parker arrived back in Australia, he spent two weeks in quarantine as a returned international traveller. But he didn’t put his feet up for long.

The Ruby Princess was making headlines, after docking at Sydney Harbour and allowing almost 2700 passengers to disembark the ship despite 13 people still awaiting COVID-19 test results.

It was a debacle that would have grave consequences, with the ship eventually being linked to more than 600 coronavirus cases and at least 22 deaths. An independent inquiry is ongoing.

Dr Parker only became involved once the ship had been relocated to Port Kembla in Wollongong, 90km south of Sydney, with more than 1000 crew members still confined to their cabins.

“It was a police operation,” Dr Parker says.

“Our job was to make the ship as safe as possible for it to set sail.”

The medical team’s first task was to take swabs and blood samples from every person on board over two days so that NSW Health could determine who was infectious.

The mass testing effort identified 40 positive cases, who were removed from the ship and put up in medical hotels.

“It was physically and mentally tiring,” Dr Parker says.

“We were working 14-hour days — not only sampling and monitoring the crew on board, but also doing all the administration and assessing the results.”

Only a small working crew were allowed out of their cabins to do essential tasks, but Dr Parker says everyone handled the isolation well.

He describes the two weeks as a “great success story” for the Ruby Princess.

His medical team worked alongside NSW Health, Border Force, the Federal Police, the Army Reserve, quarantine officials and the port authorities.

And while there might have been a war of words in the media as to who was to blame for the initial disaster, Dr Parker says there was “incredible co-operation”.

Following the quarantine, 500 crew members caught flights to their home countries while the remaining group sailed to Manila Bay in the Philippines.

Dr Parker says despite working on the front line, he never had any concern about contracting the virus himself, which he attributes to his past experiences with infectious diseases.

“It was immensely helpful because COVID-19 has a death rate of maybe 1-2%, whereas the Ebola death rate is about 70% — you don’t take any chances whatsoever,” he says.

“We had a very professional team on board, we were very competent with social distancing and PPE.”

“More than that, our experiences with Ebola taught us that if you’re careful then you can be quite safe.”

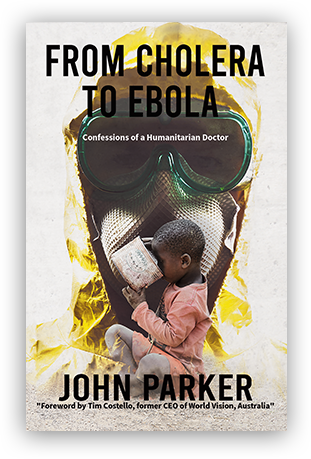

Dr Parker is a GP and the author of From Cholera to Ebola: Confessions of a Humanitarian Doctor published by Austin Macauley.

Post Views : 525